Part of my effort to see every Shakespeare play.

Richard II is one of Shakespeare’s most lyrical plays. Covering the final two years of Richard’s reign and chronicling his fall from power, it is one of only four plays entirely written in verse – there is no prose. Puns, rhyming couplets and soliloquies abound, meaning this was a terrible play to see from one of the standing spots at the Sam Wanamaker, as I did. In fairness, I chose standing after a horrific experience seeing Faustus earlier this year sitting on some of the most uncomfortable seats known to man down in the stalls, and it was less awful, but still – the thing about creating authentic seventeenth century atmosphere is that comfort is rather lacking.

I mention this very early on because I don’t want to be too unfair on a play that I didn’t really like, when someone reading this who did enjoy it might have put down my negative experience to my aching feet and clock-watching. However, it has to be said that this performance has to have been my least favourite Shakespeare play so far.

This is unfortunate because to everyone else, this performance was historical, as the Telegraph put it: “the Globe makes history with this first ever all-female, all-BAME Shakespeare”. It struck me that this didn’t seem particularly unusual or innovative to me – but gender blind-casting has only been a thing in the last fifteen years or so, so I guess for actors for whom during their training, it was going to be Othello or Ophelia or avant garde obscuria, this was a big deal to them. Perhaps it is truly a sign of progress that it just wasn’t to me. It’s also a shame that said performance just wasn’t very good.

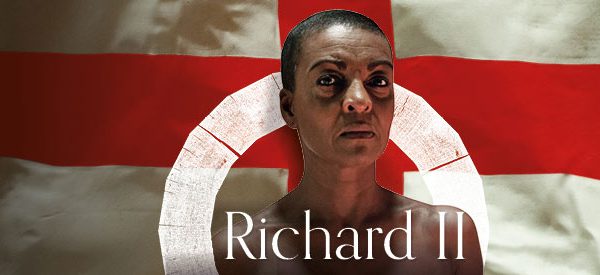

Richard II is now my fifth Shakespeare play for this project, and it’s been educational, both in terms of experiencing a massive part of my cultural heritage, but also what I specifically enjoy about them. And, as with Richard III, I watched a performance that moved a production into the modern day without any real purpose, and I just didn’t really like it very much. The promo blurb says “Adjoa Andoh and Lynette Linton direct the first ever company of women of colour in a Shakespeare play on a major UK stage, in a post-Empire reflection on what it means to be British in the light of the Windrush anniversary and as we leave the European Union.” This was reflected in the loud African chanting during the processionals, the costumes, and the decoration of the theatre with large images or the ancestors of members of the cast – all highly incongruous in an replica seventeenth century playhouse. I think the RSC does it better.

Adjoa Andoh turned in a solid performance as a King Richard II who owns the stage but slowly loses the spotlight as her kingdom is devoured by other players making the most of every poor decision, until she is finally forced to give up her crown to Henry IV in what was probably the most moving scene of the play, possibly because something actually happened in it. I guess I can kind of see the company’s argument that Richard’s slow loss of power despite his swagger as he fails to adapt to events can be read as Britain’s steady loss of Empire without the loss of any of our imperial self-confidence, but I had to sit down and think about it, hard, to make those connections.

I don’t know, I’m not convinced by a play that seems to feature more people just talking at each other than King Lear. Maybe I was just frustrated by the restricted view. Wikipedia writes almost breathlessly of other performances in history:

“The play had limited popularity in the early twentieth century, but John Gielgud exploded onto the world’s theatrical consciousness, through his performance as Richard at the Old Vic Theatre in 1929, returning to the character in 1937 and 1953 in what ultimately was considered as the definitive performance of the role. … In the 1968-1970 seasons of the Prospect Theatre Company, Ian McKellen made a breakthrough performance as Richard, opposite Timothy West as Bolingbroke. The production, directed by Richard Cottrell, toured Britain and Europe, featuring in the Edinburgh Festival in 1969 and on BBC TV in 1970. In 1974, Ian Richardson and Richard Pasco alternated the roles of Richard and Bolingbroke in a production from John Barton at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre: thirty years later this was still a standard by which performances were being judged. …Additionally the role was played by Mark Rylance at the Globe Theatre in 2003. An often overlooked production, the lead actor handles the character in, as The Guardian noted, perhaps the most vulnerable way ever seen. The play returned to the Globe in 2015 with Charles Edwards in the title role. … The Royal Shakespeare Company produced the play with David Tennant in the lead role in 2013.”

A play performed by Ian McKellen, Ian Richardson, Kevin Spacey and David Tennant seems to be a play worth watching, so perhaps for all my sore feet, this production really didn’t electrify me the way another cast might have done. I may have to try again.