Originally posted to Facebook in September 2025, but I keep going back to reread it and get excited again, so thought I’d save it for posterity. Lightly edited, mostly to add hyperlinks.

In 2007, aged 16, I went on a school trip to Rome, which involved a day trip to Herculaneum, a Roman seaside town also buried by the Vesuvius eruption but considerably less well marketed than Pompeii. Our tour guide was very attractive and very Italian, but also madly in love with Herculaneum, and he told us about the House of the Papyri, a Roman villa where in the 1850s, archaeologists had excavated an entire library of scrolls of unparalleled value to ancient literature, but no-one could read them because although perfectly preserved, they were also burnt to a crisp. Also, only half of Herculaneum is excavated because the rest has the modern town, also called Herculaneum, sitting on top of it. I remember the tour guide looking at us and saying with total conviction, “if it was up to me, I’d tear the entire town down”.

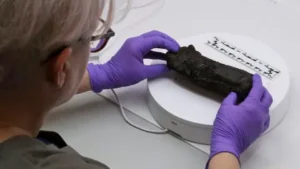

I spent the next ten years monitoring the situation with the scrolls and whether we’d worked out how to read them yet – obviously we’d have to work out how to scan them without opening them, because the ones they’d tried to open had basically fallen to bits and were destroyed and so scholars eventually stopped doing that and focussed on trying to keep them safe while awaiting the tech that would one day be invented that would read them. But very little progress was made and for a decade I was restricted to telling people that there was this ancient library of scrolls that we’d found that would likely revolutionise our understanding of the ancient world – if we could just read them.

In 2018, one Alex Mason showed up in my life and dropped a message into a chat we were having about the origins of noughts and crosses, saying, “I was reading on Reddit yesterday about how they found a load of burnt scrolls that’s probably got loads of ancient literature thought lost and they’re maybe getting somewhere with scanning them with technology, it’s really cool” and I was like ARE YOU INTERESTED IN THE HOUSE OF THE PAPYRI BECAUSE I WOULD LOVE TO TALK MORE WITH SOMEONE ABOUT THIS. A few years of monitoring the situation together pass, and the Vesuvius Prize, offering a million dollars to focus minds on the problem of developing the tech to read the scrolls, was won for the first time in 2023. And we thought, “ok, it’s time we got more involved in what’s actually happening here, this is getting real”.

So we took out joint membership of the Friends of Herculaneum Society (run by Oxford University, membership 147 – I said to Alex, I think we’ve accidentally joined a learned society of professors and the AGM’s going to be a bunch of people in bowties and us, and I was not wrong) and started following the updates they were sending out. This year they decided to mark the 21st anniversary of the Society with a free two day conference on Herculaneum (and the scrolls) in September and so we went along. Two days of badly chaired talks that kept running over because everyone is in love with Herculaneum and can’t stop talking about it. A private tour for Friends to the Greek and Roman Reading Room of the British Museum and their Herculaneum artifacts! I also took the opportunity to finally visit the Parthenon Marbles and was disappointed as I always knew I would be by all these friezes that are not giant round marbles as I have and will always imagine them to be.

But, the conference. I can honestly say I’m not sure I’ve ever been to a more interesting classics conference in my life. I don’t know how big the Herculaneum fandom is, but every big name in this field was there, from America to Italy, talking about their work and hobnobbing in the breaks. We couldn’t work out who the audience was, because it was a very white-haired conference for what is the very cutting edge of the intersection between technology and the Roman Empire, but seemingly everyone who stood and asked a question was either writing a book on Herculaneum, had been there in the last few months, or both. Brent Seales, Professor of Computer Science at the University of Kentucky, showed up and talked about how the Vesuvius Prize had led to certain breakthroughs in tomography (3D scanning) and the use of AI to identify ink. And the extraordinary thing is that this all happened because the former CEO of GitHub read a book on Ancient Rome as his summer reading and found out about the scrolls, and emailed Brent Seales to go to his unconference to give a session about it. Brent accepted, went and camped in a field in Michigan for a week, told a bunch of bright, bored wealthy guys about the tech problem, and they were like, we’re in, and broke the back of a solution that we have been working on for 150 years!

And only half of the scrolls have even been scanned so far, they’re literally having to use the fame of the Vesuvius Prize to lever the institutions to let them access the scrolls they hold, as they’re scattered around the world. A speaker said that he went to Oxford University regularly for scholarly purposes and he asked them every time he visited for years to let him see the scrolls they hold. They said it was “unthinkable” every time. They’d sat in a box on a shelf for sixty years and that’s where they were going to stay. After the Vesuvius Prize had a winner, they not only let him see them, they let him scan them, and now they’re putting on an exhibition to the public to display them. From “unthinkable” to public display. In a five year period. That’s where we’re at right now.

Alex and I also learned, to our great shock, that there’s almost certainly a second library in the unexcavated part of the Villa dei Papyri, because everything we’ve read found so far (we can decipher the writing on the outside of the scrolls so we know what texts most of them probably are) is from Greek philosophy and it seems very unlikely that the owner of this villa had one library on one subject and didn’t have a more generic working library of Roman ethics and histories. Just imagine what a perfectly preserved Roman library of a wealthy aristocrat could hold. Pliny the Elder’s 20 volume history of the German wars. The lost Annales of Ennius, the greatest poem of all of Latin literature that is entirely gone except for 600 lines preserved because it was quoted so much. Livy’s Histories, one of our primary sources of Roman history, has only come down to us in 35 books out of ONE HUNDRED AND FORTY TWO.

Imagine if it’s in that villa.

Imagine if we saved it.

Imagine if we scanned it, and translated it.

It would completely change all of classical studies for the last two thousand years forever, we’d be back at the very start of the field.

Imagine it.

The reason my school trip was to Herculaneum and not Pompeii was because a couple of academics set out in 2001 to restore the site and make it accessible to visitors. Italy does not take care of its ancient sites just because they have so many of them, and Friends of Herculaneum was founded in part to make people care. In the last twenty years, the people in that room have founded an Archaeological Park, secured the site, cleaned it, launched tours, built a tourist industry, facilitated research, sponsored PhDs, made the site available as a venue for the local community and events, and applied for various grants and funding to sponsor all of this work. That conference was the culmination of decades of effort and collaboration between different fields of scholars working across disciplines that have ostensibly little to do with each other with little credit until the breakthrough.

The breakthrough is now here, but as Brent Seales said, “this is the end of the beginning”. I just don’t think there is possibly a more exciting area of antiquity to be interested in right now. And they need people. Professor Richard Janko said in his talk about the work of actually translating the scrolls once the tech has uncovered the writing was saying that, when we finally start uncovering full passages and texts, “there are too few scholars and too many papyri” – it was heavily implied that everyone who was working on this was a) fewer than a dozen people and b) mostly sitting in the room of white hair in front of us. As Alex was saying to me in the break, “this is insane, can you think of literally any other field where you can start work on a postgrad project and the reward might be getting your name on an work of ancient literature thought lost for two thousand years that the modern world has never seen before?”

Anyway, we left inspired. It was almost stressful how exciting it was, I had to tell myself, “no, Sarah, you cannot dump your entire career and go into ancient papyri translation, you’ve got a mortgage”. At the final plenary, several people said, what can we do to help? and the answers were “learn ancient Greek and get into AI” and “tell people about Herculaneum, we need to preserve it and excavate the rest and that takes money and will”.

So this is me, telling you about Herculaneum, why you should care about it, why you should join the Friends of Herculaneum, and next time you’re in Naples, drop by Herculaneum and have a tour guide tell you why, if it was up to us, we’d tear that entire town down.

Join the Friends of Herculaneum Society.

Visit the Herculaneum Archaeological Park website.