In the late seventeenth century, a new substance was brought back from the edges of the British empire. Sociable, pleasant and healthier than tobacco, it spread first among the aristocracy, but eventually became popular with the masses, to such an extent that, although the government tried to stamp out its consumption, a massive international smuggling operation grew up around it, importing several million pounds of the stuff to supply the demands of the great British public. Only in 1784, after criminal gangs had set up their bloody fiefdoms to run rings around the government, did Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger relent and institute a proper system of control and regulation that made supplies cheap, pure and accessible to all.

I refer, of course, to tea. Many of you were probably thinking of opium, but the major smuggling network of the eighteenth century in England was centred around tea. Why? Because it was difficult to get hold of legally. Starting from 1689, high taxes were imposed on tea, starting at 25 pence in the pound and eventually reaching 119 pence. It was a bad move for the government, not least because it led to the American Revolution (the Boston Tea Party being a revolt against the high taxation of tea). But it also led to a shrinking of the market in legal tea as vendors used the illicit tea trade to offset their losses by buying illegal tea and selling it on the legal market – because tea largely looks like tea, whether taxed or not.

Up until the 1760s, the main dealers in illegal tea were small-time vendors, supplying small amounts with help of sympathetic local residents. Britain did a rather nice line in smuggling, which was a significant industry in rural England for nearly 200 hundred years in order to evade the high excise taxes imposed by a government fighting highly expensive wars against, well, everyone. Tea was added to the list of products that everyone wanted, including wool, alcohol and tobacco, but which few were able to afford. The fact that tea had to be smuggled in from the coasts also meant that the more rural population of the UK was introduced to what had hitherto been a cosmopolitan aspiration.

It is interesting to note that for twenty years prior to the smuggling explosion, the existence of tax-free tea had little effect on the legal trade. It was only as customs imposed higher and higher taxes that people began to look elsewhere for their tea. One might consider that tobacco is in something of the same boat today.

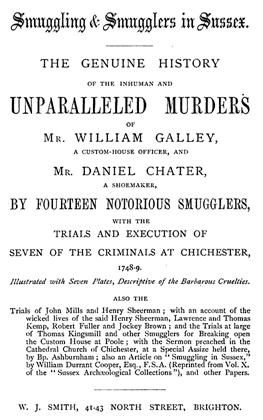

Where there is a criminal element, there is violence. As early as 1747 the Hawkeshurst gang in Poole attacked a customs house killing the customs officials and taking back the tea that had been confiscated from them. By the 1770s, however, the trade had expanded dramatically, and less scrupulous “investors” had discovered the lucrative illegal tea trade. Heavily armed ships carrying tax-free tea and spirits began to appear off British coasts. Indeed, “the illicit tea trade had achieved a system unexampled in the checkered history of smuggling.” (Hoh-Cheung and Mui, pg 58.)

In 1784, the East India Company and the London tea traders, unable to compete with the black market, had had enough and petitioned Prime Minister Pitt to reduce the tax on tea. The Commutation Act 1784 was passed, reducing the tax on tea from 119% to just 12.5%. With legal tea suddenly much more affordable, and quality much higher, the smuggling trade was virtually stopped overnight.

I’m sure you can see what I am getting at here. What the effective Prohibition of tea in the eighteenth century can teach us today is that if people want to consume a drug, it will be supplied. Even if that drug is legal, but authorities seek to make it unavailable, resourceful citizens will find a way. One wonders what will happen if Manchester City Council has its way and introduces minimum alcohol pricing – because I’m willing to bet on enterprising syndicates, of both local neighbourhood and criminal gang types, getting together to avoid the charge.

However, the history of the illicit tea trade is not entirely ominous. Hoh-Cheung and Mui argue, “What appeared from the viewpoint of the law to be frauds, abuses, and evasions, might also be regarded as innovations promoting the international and domestic trade of the kingdom, which, in turn, contributed to the growth of the British economy in the latter part of the eighteenth century.” But how much of that growth did the taxman see? Eventually the government woke up to the fact that people wanted to drink tea but weren’t prepared to pay through the nose for it. In 1784, the Prohibition of tea ended – how much longer until the current government realises you can’t legislate drugs out of existence?

For further reading on the illicit tea trade, try reading Smuggling and the British Tea Trade before 1784 by Hoh-Cheung and Lorna H. Mui.

Or visit the UK Tea Council, who have lots of interesting information on the history of tea.

Subscribe to SarahMcCulloch.com via Email! (or via RSS!)

Another important aspect is that if you are an older person, travel insurance with regard to pensioners is something you ought to really look at. The more mature you are, the harder at risk you happen to be for having something terrible happen to you while in another country. If you are not necessarily covered by many comprehensive insurance plan, you could have quite a few serious challenges. Thanks for revealing your suggestions on this blog.